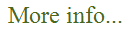

1935 Joe Cronin Baseball Hall Of Fame Vintage Photo 7x9 Inches Bat Holding

A GREAT VINTAGE 7X9 INCH PHOTO FROM 1935 DEPICTING THE HALL OF FAMER JOE CRONIN WITH A CLOSE-UP OF HIM HOLDING HIS BAT. Star player, manager, general manager, league president-only one man in baseball history has followed a career path like this one. Joe Cronin, one of the greatest shortstops in the game's history, spent 50 years in the baseball without being fired or taking a year off.

Every job was a promotion, and he came within a whisker of being baseball's commissioner in 1965. Late in life, reflecting on all his contributions and responsibilities over the years, Joe made it clear where his heart lay.

"In the end, " said Joe, the game's on the field. Joseph Edward Cronin was born in San Francisco on October 12, 1906, six months after the great earthquake and fire that devastated his home city. His father, Jeremiah, born in Ireland in 1871, had immigrated to San Francisco in either 1886 or 1887 in search of an easier life, but had found mostly hard work in the years since. His wife, Mary Carolin, was a native of the city, and the couple had two other boys-Raymond b. December 1894 and James b.Joe's brothers being much older, he was blessed with a lot of time to play sports, which neither of his brothers had done. San Francisco had a well-established system of playgrounds, with directors responsible for organizing teams in different sports, and playing games against other playgrounds. The Excelsior Playground, as luck would have it, was one block from the Cronin house.

Joe, a strong youth who grew to nearly 6 feet tall as a teenager, played soccer, ran track, and won the boys' city tennis championship in 1920. But baseball was his first love, as it was for most athletes in the city. Though there were no major-league teams west of St. Louis, the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League became like the major leagues for the local fans. In addition, many San Franciscans had played for the Seals and then made good in the majors, including George Kelly, Harry Heilmann, and Ping Bodie, one of Joe's early heroes.

In 1922 Joe teamed up with Wally Berger to help win the city baseball championship at Mission High. The following summer the school burned down, and while it was being rebuilt, Joe transferred to Sacred Heart, a Catholic school a few miles north of his home. Joe starred in several sports at his new school, and his baseball team won the citywide prep school title in 1924, his senior year.By this time, Joe was also playing shortstop with summer clubs and for a semipro team in the city of Napa, north of San Francisco. Although Cronin had long dreamed of playing for the Seals, he passed up an offer to join the San Francisco club by taking a higher offer from scout Joe Devine of the Pittsburgh Pirates in late 1924. In the spring, Joe trained with the Pirates in Paso Robles, California, but soon joined the Johnstown club of the Middle Atlantic League, hitting. 313 with just three home runs but 11 triples and 18 doubles in 99 games. At the end of the season, Joe and his friend and roommate Eddie Montague joined the Pirates, working out with major leaguers and sitting on the bench while Pittsburgh beat Washington in the 1925 World Series.

The Pirates were a strong club, especially at the positions Joe would most likely play. Shortstop Glenn Wright and third baseman Pie Traynor were among the best at their positions in the game, and the 19-year-old Cronin had very little hope of playing much in 1926. He traveled with the team early in the season, pinch-running four times and scoring two runs, before being assigned to New Haven in the Eastern League. This club was operated by George Weiss, near the start of a long career in the game that would eventually land him in the Hall of Fame. By midsummer, Cronin was hitting. 320 and earned another recall to the Pirates. In the latter stages of the season Joe played 38 games, mostly at second base, a position he had never played. 265 for manager Bill McKechnie, a promising start for the youngster.After the season McKechnie was fired, and the new manager, Donie Bush, moved George Grantham from first to second base, blocking Cronin's best path. Joe stuck with the 1927 club the entire season, but played just 12 games, hitting 5-for-22. The Pirates won the NL pennant again, but Joe had a miserable time and hoped to play in the minors rather than sit on the bench again. He was back in the minor leagues.

282 with eight home runs and 29 doubles. His 62 errors, due mainly to overaggressive throwing, did not cause alarm. Turning 22 that fall, Cronin was one of the brightest young players in the game.

In fact, the baseball writers voted Joe the league's MVP, ahead of Al Simmons and Lou Gehrig. It was not until 1931 that the writers' award became the "official" MVP award, but Cronin was recognized in the press as the recipient in 1930.

Lefty Grove hunted and drank with the owner, who looked the other way when his star pitcher openly blasted Cronin in the press. Ferrell apparently never paid his fine for storming off the mound. The Red Sox continued to acquire controversial veterans, players who had had trouble with managers over their careers, and invariably they caused trouble with Cronin. When Collins finally succeeded in dealing Ferrell (along with his brother Rick, who caused no trouble) in 1937, the club acquired Bobo Newsom and Ben Chapman, two of the bigger managerial challenges in the game.

After a fine year at bat in 1935.295 with 95 runs batted in, Joe suffered through a frustrating season in 1936. The acquisition of Jimmie Foxx and others from the Athletics made the Red Sox a supposed pennant contender, but Joe's injury-plagued season a broken thumb limiting him to 81 games and a. 281 average helped the Red Sox finish a disappointing sixth. At this point many observers thought Joe, overweight, struggling in the field, and injured, might be through at just 30 years old. Instead, Joe rebounded to hit. 307 with 18 home runs and 110 RBIs in 1937, then.The Red Sox won 89 games in 1939, and Joe had another fine year. 308 and 107 runs batted in.

Joe's biggest problem in these years was the Yankees, who were one of history's greatest teams. It was not any great shame to finish second to the Yankees in this era, and the Red Sox did so four times in five seasons beginning in 1938. 285 with a career-high 24 home runs in 1940, then. 311 with 95 runs batted in 1941. After his All-Star season in 1941, he quietly stepped aside for rookie Johnny Pesky in 1942. Even with Pesky in the Navy for three years beginning in 1943, Cronin was mainly a utility infielder and pinch-hitter (setting a league record with five pinch home runs in 1943) during the war years. In April 1945 he broke his leg in a game against the Yankees, missed the rest of the reason, and hobbled away from his playing career. In the heavily Irish culture of 1930s Boston, the Irish and personable Cronin remained personally popular with the fans and press. Even otherwise critical stories invariably mentioned what a swell guy he was. By the 1940s, Cronin was no longer the young upstart manager, but was a veteran on a team that was developing young talent. The new generation, men like Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr, admired and respected Cronin. With his stars back and Cronin a full-time manager for the first time in 1946, the Red Sox cruised to the pennant but lost a seven-game World Series to the Cardinals. With most of the star players save Williams having off-years or hurting in 1947, the club fell back to third place. At the end of the season, Cronin took off his uniform for good, replacing the ill Eddie Collins as the club's general manager. In Cronin's first act in his new role, he hired Joe McCarthy as his new manager. These deals catapulted the team back into contention again, but they lost two heartbreaking pennant races in 1948 and 1949. During Cronin's 11-year tenure running the franchise (as general manager, president, and eventually treasurer), the team evolved from a contender to a middle-of-the-road club. The biggest problem, though by no means the only one, was the club's failure to field any black players. The Red Sox famously had first crack at Jackie Robinson in 1945, and at Willie Mays in 1949. By 1958, Cronin's last season as general manager, more than 100 blacks (either African-Americans or dark-skinned Latins) had played in the majors, 11 of whom went on to the Hall of Fame.None of the 100 played for the Red Sox. Joe and Mildred had four children-Thomas Griffith (named after Yawkey and Clark Griffith, born 1938), Michael (1941), Maureen (1944), and Kevin (1950). They bought a house in Newton, just outside the city of Boston, in 1939 and settled there.

When AL President Will Harridge was first rumored to be stepping down in October 1956, Cronin was thought to be the obvious successor. When Harridge finally quit two years later, Cronin was quickly hired to succeed him. In deference to Cronin, the league office was moved from Chicago to Boston.

Cronin scouted the new offices himself, settling on a location in Copley Square. His principal role was to preside over league meetings, building consensus to solve the problems of the moment. The leagues had much more power than they do today-leagues had their own umpires, could expand or move teams without consulting the other league, could have their own rules, their own schedules. During his 15 years running the American League, Cronin oversaw the league's expansion from eight to 12 teams, and orchestrated the relocation of four teams.

In 1966, while league president, Cronin hired Emmett Ashford, the first black major-league umpire, nearly seven years before the National League integrated. In a later interview with Larry Gerlach, Ashford praised Cronin for having the guts to hire him: Jackie Robinson had his Branch Rickey; I had my Joe Cronin. Cronin was twice a leading candidate for the commissioner's job: in 1965, when Ford Frick resigned, and again when William Eckert was forced out in 1968. Cronin ran the American League until 1973, the year the league introduced the designated hitter rule, a rule he did not like but which he helped write. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn wanted to move the two league offices to New York, where the commissioner's offices were. Cronin did not want to move, and he chose to retire instead. At the end of his final season, he was given the ceremonial title of American League chairman. Joe spent a life in the game, and he was renowned for his good works outside the game.He set up the Red Sox' initial connection with the Jimmy Fund, which became the team's signature charity after its original sponsor, the Boston Braves, left town, and worked with the fund for many years. He received dozens of honors for his work outside the game. Joe Cronin entered the Hall of Fame in 1956, with his longtime friend and rival Hank Greenberg-they were rivals as players, and at the time of induction they were rival general managers. The Red Sox retired his number 4 on May 29, 1984; on the same rainy evening they retired Ted Williams' number 9-the first two numbers the Red Sox officially put out of service. Joe was dying of cancer, and the ceremony was pushed ahead to ensure that he could attend.

He made it to that park that night, but was only able to wave to the crowd from a suite high above the field. Williams was there, and praised his former manager and longtime friend. After waving to Joe, he told the crowd how important Cronin was to him.

Joe Cronin was a great player, a great manager, a wonderful father. No one respects you more than I do, Joe. In my book, you are a great man.After a long battle with cancer, Joe passed away on September 7, 1984, leaving his beloved Mildred and their four children. He may be the least known of the honorees on Fenway Park's right field façade, but no man had a greater impact on Red Sox history than Joseph Edward Cronin. Every Day I put on a uniform was a thrill. Just to be a part of the show was a real thrill for me.

Every day could have been my first big league game. Joe Cronin had one of the most interesting, multifaceted careers in baseball-he was a player, manager, general manager, American League President, and a member of the Hall of Fame's board of directors and Veteran's Committee.He played part of the 1926 season in Pittsburgh, but spent most of the time with the New Haven minor league team. Where he was promptly spotted by Joe Engel, a scout for the Senators. The next year he made his mark on the game by hitting. 346 and being selected as the American League's most valuable player. In 1933, Clark Griffith, the Senators' owner, made Cronin player-manager, and under Cronin, who hit.

309, led the league in doubles and led the league's shortstops in fielding, the Senators won the pennant. But they lost the World Series to the New York Giants. The next year proved disastrous as the Senators dropped to seventh place, but during the All-Star Game Cronin earned part of a special footnote to baseball history. He was one of five future Hall of Famers, including Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, who were struck out in succession by Carl Hubbell.After the 1934 season, Cronin married Griffith's niece and secretary, Mildred Robertson. Cronin continued as an active player until he broke a leg in July 1945, but he had taken himself out of the regular lineup in 1942.

The Red Sox did not win a pennant with Cronin as manager until 1946, when the club won 104 games but lost the World Series to the St. After retiring as field manager in 1947, he served 11 years as a Red Sox executive before being named president of the American League in 1959. In his 14 years in the job, Cronin oversaw the expansion of the league from 8 to 12 teams, stirred controversy when he dismissed two umpires for''incompetence'' after he learned they were trying to form a union in 1970 and ended his career in further controversy when he vetoed the Yankees' effort to hire the Oakland A's manager, Dick Williams, while approving the Detroit Tigers' signing of the Yankees' former manager, Ralph Houk. In addition to his wife, he is survived by three sons, Thomas, Michael and Hayward; a daughter, Maureen Hayward, and several grandchildren. A funeral service will be held at 11 A.Reese was eventually traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he went on to a Hall of Fame career. [5] As it turned out, Evans' and Yawkey's initial concerns about Cronin were valid.

His last year as a full-time player was 1941; after that year he never played more than 76 games in a season. Over his career, Cronin batted.Notably, Cronin once passed on signing a young Willie Mays and never traded for an African-American player. [6] The Red Sox did not break the baseball color line until six months after Cronin's departure for the AL presidency, when they promoted Pumpsie Green, a utility infielder, from their Triple-A affiliate, the Minneapolis Millers, in July 1959. In January 1959, Cronin was elected president of the American League, the first former player to be so elected and the fourth full-time chief executive in the league's history.

When he replaced the retiring Will Harridge, who became board chairman, Cronin moved the league's headquarters from Chicago to Boston. Cronin served as AL president until December 31, 1973, when he was succeeded by Lee MacPhail. During Cronin's 15 years in office, the Junior Circuit expanded from eight to 12 teams, adding the Los Angeles Angels and expansion Washington Senators in 1961 and the Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots in 1969. It also endured four franchise shifts: the relocation of the original Senators club (owned by Cronin's brother-in-law and sister-in-law, Calvin Griffith and Thelma Griffith Haynes) to Minneapolis-Saint Paul, creating the Minnesota Twins (1961); the shift of the Athletics from Kansas City to Oakland (1968); the transfer of the Pilots after only one season in Seattle to Milwaukee as the Brewers (1970); and the transplantation of the expansion Senators after 11 seasons in Washington, D. To Dallas-Fort Worth as the Texas Rangers (1972).

The Angels also moved from Los Angeles to adjacent Orange County in 1966 and adopted a regional identity, in part because of the dominance of the National League Dodgers, who were the Angels' landlords at "Chavez Ravine" (Dodger Stadium) from 1962-65. Of the four expansion teams that joined the league beginning in 1961, three abandoned their original host cities within a dozen years (the Pilots after only one season), and only one team-the Royals-remained in its original municipality.

Two of the charter members of the old eight-team league, the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians, also suffered significant attendance woes and were targets of relocation efforts by other cities. In addition, the AL found itself at a competitive disadvantage compared with the National League during Cronin's term. With strong teams in larger markets and a host of new stadiums, the NL outdrew the AL for 33 consecutive years (1956-88). [7] In 1973, Cronin's final season as league president, the NL attracted 55 percent of total MLB attendance, 16.62 million vs. 13.38 million total fans, despite the opening of Royals Stadium in Kansas City and the American League's adoption of the designated hitter rule, which was designed to spark scoring and fan interest. While the National League held only an 8-7 edge in World Series play during the Cronin era, it dominated the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, going 15-3-1 in the 19 games played from 1959-73. After the 1968 season, Cronin drew headlines when he fired AL umpires Al Salerno and Bill Valentine, ostensibly for poor performance; however, it later surfaced that the two officials were fired for attempting to organize an umpires' union. Neither man was reinstated (Valentine became a successful minor league front-office executive), but the Major League Umpires Association was formed anyway, two years later. [8] However, in 1966, Cronin was hailed for integrating MLB's umpiring staff with the promotion of veteran minor league arbiter Emmett Ashford to the American League. Joe Cronin's number 4 was retired by the Boston Red Sox in 1984.[10] Cronin came to Fenway Park for one of his last public appearances when his jersey number 4 was retired by the Red Sox on May 29, 1984. He died at the age of 77 on September 7, 1984, at his home in Osterville, Massachusetts. [11] He is buried in St. Francis Xavier Cemetery in nearby Centerville.

At the number retirement ceremony shortly before Cronin's death, teammate Ted Williams commented on how much he respected Cronin as a father and a man. Cronin was also remembered as a clutch hitter. Manager Connie Mack once commented, With a man on third and one out, I'd rather have Cronin hitting for me than anybody I've ever seen, and that includes Cobb, Simmons and the rest of them. In 1999, he was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs". The seller is "memorabilia111" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Republic of Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam.